https://www.ft.com/content/cf51e840-7147-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

The UK economy since the Brexit vote — in 6 charts

Government talks of deal dividend as uncertainty hits business confidence and investment

Chris Giles, Economics Editor, and Keith Fray, Statistics Editor October 11, 2018

As Brexit negotiations reach a climax, how is Britain’s economy doing?

Both remainers and leavers acknowledge that since the nation voted to leave the EU two years ago the data have been disappointing but not disastrous.

Now, however, uncertainty over the outcome has reached new highs. Prime Minister Theresa May’s talks with the EU in the next few weeks could make the difference between a relatively smooth departure from the bloc and a no-deal exit.

The doubts have eaten away at business confidence and investment. But consumers were happy to spend freely in the hot weather over the summer and there are only tentative indications that they are now reining back as the nights draw in.

This balancing act is likely to continue until either Mrs May strikes a Brexit deal with Brussels and shepherds it through parliament — or, alternatively, negotiations fail.

Philip Hammond, UK chancellor, argues that a good outcome could yield a “deal dividend” and an upgrade to economic and public finance forecasts. No deal would bring further downgrades.

These six charts — including indicators on spending, saving and stock market indices — show how the UK economy is faring with less than six months to go until Britain’s departure from the bloc.

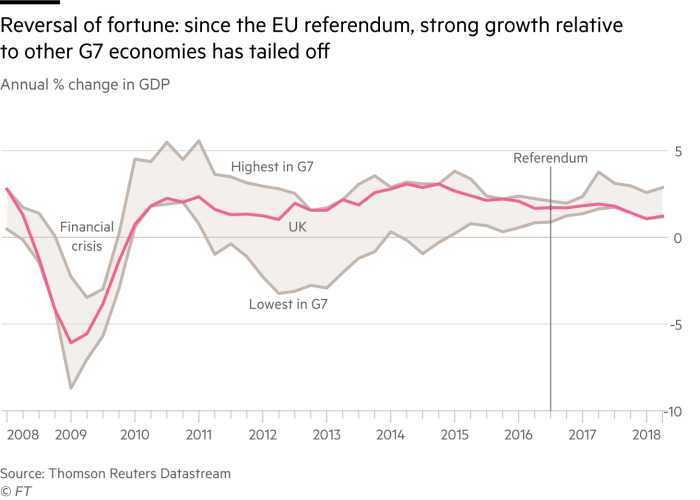

1. The overall performance of the UK economy

https://www.ft.com/content/cf51e840-7147-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

Britain’s growth rate bounced back in the second quarter to a 0.4 per cent rate, from 0.1 per cent at the start of the year, when activity across the UK was hit by snowstorms and a prolonged cold snap. With a hot summer encouraging spending, the rolling quarterly rate further increased to 0.7 per cent in the three months to August.

That does not pull the UK much off the bottom of the G7 league table for annual growth; the UK sat just above Italy in the second quarter. Financial Times research has shown that by the end of the first quarter, the UK economy was between 1 and 1.5 per cent smaller than it would have been without the Brexit vote, although some independent estimates, such as a recent report from the Centre for European Reform, suggest the hit could have been as large as 2.5 per cent.

Julian Jessop, the Brexit-supporting chief economist of the Institute of Economic Affairs, a free-market think-tank, said such estimates were likely to be too high, but he accepted that the referendum had depressed economic performance so far, although he thought that was likely to be a temporary effect.

“The UK economy has probably grown more slowly due to the additional inflation prompted by sterling’s fall, and the heightened uncertainty,” he said.

2. The remarkable strength of employment

https://www.ft.com/content/cf51e840-7147-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

With the unemployment rate down to 4 per cent between March and May, its lowest rate since the mid 1970s, the labour market has strengthened significantly since the EU referendum. This is the glaring exception to otherwise disappointing data. Not only is employment up, but most of the growth has been in full-time jobs. The number of people in part-time jobs and in self-employment is now falling gently and more than offset by the rise in full-time work, reducing concerns that people are underemployed.

The end of the boom in self-employment has also reduced concerns that people were setting up in business because they could not find any other work.

The one fly in the ointment in the jobs numbers is that employment growth rates now appear to be tailing off, with overall employment growing by only 3,000 in the second quarter of 2018 compared with a rise of almost 150,000 from January to March. The shift in employment rates is especially marked for people born in other countries: 5.6m of them were working in the UK in the second quarter of this year, 1 per cent less than in the same period in 2018.

3. Wage growth has been hit by higher inflation

https://www.ft.com/content/cf51e840-7147-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

Not all is rosy in the labour market. Although wage growth has risen a little, real wage increases dropped away after the Brexit vote as inflation climbed well above the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target. Prices rises have recently exceeded expectations and wage increases have been struggling to match them.

Productivity growth has also continued to disappoint. However, this is not a new post-Brexit vote development but extends a trend that has existed since the financial crisis. Occasional false dawns in productivity improvements have not been sustained.

4. Households have thrown caution to the wind

https://www.ft.com/content/cf51e840-7147-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

With wage increases not matching price rises in 2017 and 2018, household real incomes have faced a nasty squeeze. But Britain’s consumers appear to have thrown caution to the wind ever since the EU referendum, increasing borrowing and lowering savings to spend today rather than tomorrow. In the second quarter of 2018, households saved 3.9 per cent of income, up a fraction on the first quarter, but this still represented half the 7.8 per cent rate at the start of 2016. The savings rate is at a historical low.

As a corollary of this, the household sector has moved into a net financial deficit, borrowing more than it is saving for the first time since 1988.

Households clearly think Brexit will not hurt their finances and are spending as if the income squeeze of 2017 and 2018 was just a pinprick. The danger for the economy is that if households seek to save at normal levels once again — the 50 year average is around 9 per cent rate — spending will take a big knock as will the wider economy.

5. Companies are reluctant to invest

https://www.ft.com/content/cf51e840-7147-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

Business investment continues to disappoint, with the volume of plant, machinery and new buildings having barely grown in the UK since the EU referendum.

An economy at full employment is normally one that stimulates plenty of new business investment, as companies adopt new technologies to keep expanding without hiring new staff.

This was happening until mid-decade, but since then a combination of the drop in oil prices and the uncertainties surrounding the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, the 2015 election and the 2016 EU referendum have caused companies to think twice before committing themselves.

The latest data show a downbeat picture, with investment only 2 per cent higher than at the time of the Brexit vote and 0.2 per cent lower than a year ago.

Before the referendum, the BoE had expected business investment to have grown more than 13 per cent over the two-year period from 2016.

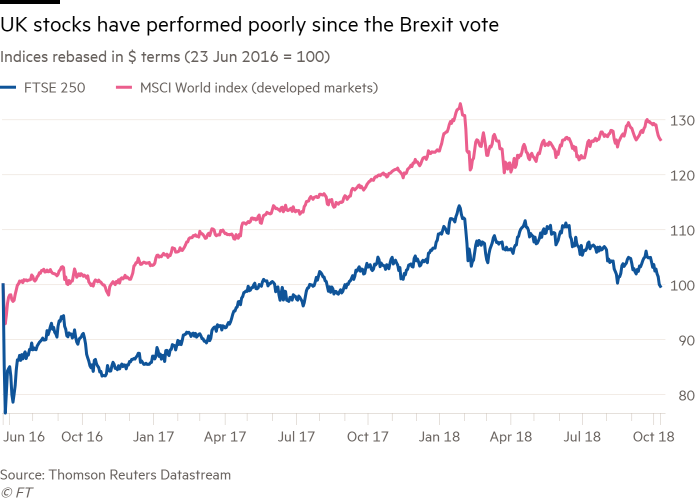

6. Investors still mark down UK assets

The performance of stock markets reflect investors’ views of a country’s economic potential.

International investment in UK shares is best measured in dollar terms by the FTSE 250 index, which is made up by companies that collectively get most of their revenues from the UK. This has slid 0.3 per cent since the 2016 Brexit vote. (In sterling terms it has risen 12 per cent.)

In the meantime the stock markets of other developed economies have risen 26 per cent, showing that investors have devalued UK assets.

https://www.ft.com/content/cf51e840-7147-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9